In my previous two blogs I outlined the factors which are responsible in determining access to renewable fresh water resources in urban areas, both physical and socioeconomic. However, what does access really mean? Is it equivalent to the availability and access that I am used to in London on a daily basis?

|

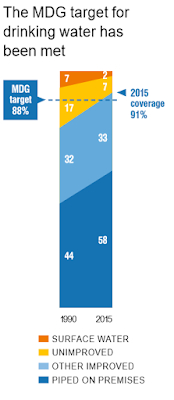

| Figure 1: Trends in global drinking water coverage and MDG target (%), 1990-2015. Source WHO/UNICEF (2015) |

The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP), which began in 1990, is rightfully proud of global achievements on sanitation and drinking water in the time it has provided estimates of progress towards the Millennium Development targets. In its 2015 update and MDG assessment it was able to report (fig. 1) that 91% (up from 76% in 1990) of the global population now uses an improved drinking water source with the global MDG target for drinking water met back in 2010, 5 years ahead of the deadline. An impressive 2.6 billion people have gained access to an improved drinking water source since 1990. However, in 2015, 663 million people still do not have access to improved drinking water sources.

Access to safe water as defined by the JMP in the early 1990s is the proportion of population with access to an adequate amount of safe drinking water located within a convenient distance from the user's dwelling (UNICEF/WHO, 2015). Interestingly the words in bold (and placed in small print) are defined at a country level. However the WHO suggest when no definitions are available at the country level the following definitions may be used (WHO, 1996):

- Access to water: In urban areas a distance of not more than 200m from a home to a public standpost may be considered reasonable access. In rural areas, reasonable access implies that the housewife does not have to spend a disproportionate part of the day fetching water for the family's needs.

- Adequate amount of water: Twenty litres of safe water per person per day. (For reference average water use ranges from 200-300 liters per person per day in most European countries (UN, 2014)).

- Safe water: Water that does not contain biological or chemical agents directly detrimental to health. It includes treated surface water and untreated but uncontaminated water from protected springs, bore-holes, sanitary wells, etc.

- Convenient distance: In urban areas, to fetch 20 liters of safe water per person per day, 200 meters would be a 'reasonable' distance from the home.

On the 28th of July 2010 the United Nations explicitly recognized the human right to water and sanitation. However issues of access again prevail. Sufficiency is defined as a slightly higher 50 to 100 litres per day. Although everyone has the "right to water and sanitation service that is physically accessible" (UN, 2014), the source only has to be within 1000 metres of the home and collection time should not exceed 30 minutes. This surely cannot be called accessible?

Examples of issues surrounding access within academic literature are common. For instance within urban areas in East Africa, the Drawers of Water 2 study (Thompson et al. 2000) found that a deterioration of piped water supplies occurred between 1967 and 1997 resulting primarily form a lack of system maintenance. Access still remained as defined by unicef/WHO, however true access declined as represented by a significant reduction in per capita water usage for piped households from 120.4 litres to 64.2 per day.

Furthermore, the unpredictability of piped water supply in Urban East Africa has forced households to mitigate. This is exemplified through the number of households who are storing water at home (increasing from only 3% in 1967 to 90% in 1997), in addition to their piped supplies to cater for shortages and intermittent failures (Thompson et al. 2000). Taylor (2004) reports that rapid urbanisation in east and southern Africa has overwhelmed many urban, piped supplies, forcing consumers to draw water from a mix of source throughout the year undermining true access. Similar findings have also been echoed in studies of Urban Uganda (Howard et al. 2002). True access is again debatable.

The growing demand for water in urban areas has also lead to a significant rise in private water-vending. Although this can be received positively though increasing convenience and reliability, (Thompson et al. 2000) suggest that it can be detrimental leaving households with limited choice, with rising costs closely linked to declining per capita consumption. For unpiped households, sources of water range from unprotected or surface sources through protected improved sources and private sources such a vendors. Even through protected sources are associated with accessibility, the Drawers of Water paper highlights how they are susceptible to technical failures, facing high demand and steep competition.

Water accessibility measures also fail to take into account issues surrounding collection times. Within a study in rural Ethiopia (different characteristics from urban areas, but still important nonetheless), during drought conditions collection times increased to 9 hours in places. Even within the wet season collections times are significant at 1-2 hours. Furthermore, the main constraint reported by poorer households was their inability to release labour for water collection accentuated by seasonal variability in water resources (Tucker et al. 2014). Although use of water for drinking and cooking does not decline in the dry season, water used for personal health and hygiene was found to be forfeited. Although water may be fundamentally available it is not accessible in reality as other significant costs are incurred, impacting the poorest households the hardest. In addition, the study also tackled the assumption that just because an improved resource is available it will be used preferentially. However, the study found that poorer households are

more likely to choose an unimproved source over a more expensive protected

source highlighting again how definitions of accessibility do not take into account the true reality of life on the ground. Finally, hidden within metrics of accessibility is the exacerbation of issues of gender inequality. Household collection is primarily conducted by women, and they are therefore preferentially effected with Swahili proverb stating that women are water - mwanawaki ni maji (Taylor 2004).

All these variables undermine definitions of water accessibility. Although significant improvements have been made in water availability and accessibility over the last 20 years, as the JMP recognizes, much still remains to be done. However, as I hope this blog begins to set out the problem is even greater than the JMP report outlines. This is fundamentally because definitions of accessibility hide a significant number of problems that are still at large. It is a lot easier to improve accessibility figures if you do not raise the bar high enough. At the moment access by no stretch of the imagination means full access, to the extent that people deserve as a fundamental human right.

Nice post, looks like we’re writing about the same kind of stuff. Have you taken a look at any of the readings on informal settlements? It seems to me like there’s a pretty big contrast in terms of access between them and the wider urban context.

ReplyDelete